Or face consequences.

The issue is described in a letter, authored by Kansas Attorney General Kris Kobach and joined by many others, to bank chief Brian Moynihan.

It’s over the bank’s practice of “de-banking,” or simply shutting down the accounts and banking rights, of various people and groups with whom to bank disagrees.

The letter, bearing the signatures of officers from Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah and Virginia, too, calls on Moynihan to deliver, within 30 days, a report about his “account-cancellation policies and practices,” his “risk tolerance,” “reputational risk,” “hate” and “intolerance perspectives, and “whether Bank of America considers a customer’s speech or religious exercise—or public perception or other groups’ perception of them—as a component of those policies.”

The letter told Moynihan, “It is nearly impossible to function today as an individual, family, or organization without a bank account, a credit card, and the ability to obtain a loan. Federal and state governments recognize the necessity of these kinds of financial services, which is why they have passed numerous laws to prohibit various types of discrimination in the past. It is also why national banks like yours receive bailouts and many other privileges, courtesy of the American taxpayers.”

However, the letter charges, his bank “appears to be conditioning access to its services on customers having the bank’s preferred religious or political views.”

“This is inconsistent with your bank’s promise to uphold ‘the highest standards of corporate governance and ethical conduct [including] efforts to always do business the ‘right way for [its] customers.’ Surely Bank of America would not say that denying service to clients for exercising their civil liberties is doing ‘business the right way for [its] customers.’ Your discriminatory behavior is a serious threat to free speech and religious freedom, is potentially illegal, and is causing political and regulatory backlash.”

Already, the company has built a reputation for denying services to gun manufacturers and others, fossil-fuel producers, private prisons and “conservative and religious Americans.”

Further, the bank “willingly participated in … financial surveillance” of Americans, the letter said.

“We are deeply concerned that Bank of America is willing to cooperate in the infringement of its customers’ constitutional and privacy rights to help federal law enforcement surveil and target millions of conservative Americans, many of whom live in our states. Bank of America has a pattern of viewpoint-based debanking.”

And in egregious actions, Bank of America canceled the banking accounts of multiple Christian ministries.

The letter asks the bank to “curb” its “discrimination.”

A report from the ADF explained, “Just last month, the U.S. House Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government singled out Bank of America for voluntarily handing over confidential customer information to government agencies without a warrant and without notifying its customers. Government agencies had flagged ADF and other mainstream religious and conservative organizations as ‘domestic terrorist’ threats, urging major banks to disclose private transactions involving keywords like ‘Cabela’s,’ ‘Dick’s Sporting Goods,’ and ‘religious texts.'”

The report noted the bank’s annual shareholder meeting is just days away, on April 24, at which board faces a request for a report on the “risks of politicized de-banking.”

Potentially, the report explains, there are “numerous legal and regulatory risks” the bank is embracing.

Content created by the WND News Center is available for re-publication without charge to any eligible news publisher that can provide a large audience. For licensing opportunities of our original content, please contact [email protected].

]]>Can you explain how commodity-backed currencies, like the gold standard, work with regards to saving and lending? As I understand it, with fiat money, if A deposits $1,000 in the bank, which then lends $800 to B, there’s now $1,800, but with a gold standard there’s still only $1,000. Would A only have access to $200 + whatever B has repaid? Where would the extra money for interest paid by B to the bank and by the bank to A come from? If B skips town, is A out $800?

Also, can you explain what would make a good commodity to back a currency? Would a plutonium standard, a distilled water standard, or prime rib standard work as well as a gold standard or silver standard?

To tackle the first question, we need to highlight the differences between a currency system and a banking system. Let’s start there.

Commodity vs. Fiat Money

So does commodity money, like a gold-standard, conflict with how banks operate today? Not really. To understand why, we need to get to the fundamental difference between commodity money and fiat money—redeemability.

A commodity money is redeemable for some quantity of a physical commodity. For example, we can imagine a paper currency which could be redeemed for one ounce of silver, gold, plutonium, or prime rib. If you can, in principle, take the note to a bank or government office (depending upon the specifics of the system) and have it redeemed for gold, the currency is a gold-backed currency.

Fiat currency, on the other hand, is only redeemable in itself. In other words, if you take your currency to a bank or government office in a fiat system to redeem it, they are going to hand you back different fiat currency. If you redeem your five dollar bill, the only thing you’re promised is five slightly different colored bills with Washington’s face rather than Lincoln’s.

This is the difference between fiat and commodity systems.

So, is a commodity-based monetary system compatible with banking as we know it today? Sure. Let’s run through an example to see why.

Let’s say you deposit $1,000 worth of gold at a bank. In exchange you receive $1,000 of redeemable gold-backed notes, which you can use to purchase products. If the notes are transferred, the person who receives them can redeem them for their portion of the gold. The bank has the gold it would be required to give for redemption.

In some historical government money systems, the government offers the right to gold redemption rather than the private bank, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imagine banks or private gold redemption businesses taking this on. For our purposes, we’ll just assume that the banks store gold for redemption and allow customers to save their notes. This system is maybe overly simple compared to reality, but it makes our example a bit easier.

You decide that instead of spending your gold notes, you’d prefer to save them, and you deposit the notes in the bank as well.

Someone comes along and borrows notes from the bank. The bank gives the borrower $800 worth of gold-backed currency from the $1,000 you deposited in the bank. So now, your bank account balance is $1,000 (recorded on the bank’s ledger), and the borrower has $800 in physical cash. This sort of banking system where the bank only keeps a fraction of the money deposited and lends out the rest is known as fractional reserve banking.

At this point, you may have noticed the problem that Kyle noticed. The bank essentially created new money when it loaned your money out to someone else. There is now $1,800 worth of promises to redeem currency in gold out there, but the amount of gold hasn’t changed. There’s still only $1,000 worth of gold. So is this an issue?

Well, it’s only an issue for the bank if everyone decides to redeem their currency for gold at the exact same time. In that case, the bank would be unable to meet its obligations, and it would go under unless something changed.

You might take this possibility as evidence that commodity-backed money is incompatible with fractional reserve banking. There’s two reasons why this isn’t necessarily the case.

First of all, this potential problem is not unique to commodity money. If banks hold fractional reserves in a fiat money system the same issue still applies. If every depositor runs to the bank and demands their fiat money, a bank will be unable to fulfill that obligation if they only kept a fraction of the fiat and lent out the rest.

In other words, this risk associated with fractional reserve banking is not specific to a commodity or fiat system. The risk of too many customers trying to secure funds exists in both systems. The type of money (commodity or fiat) is a separate question from the type of banking system (fractional or full reserves).

Second of all, as long as the bank keeps enough gold on hand to meet the actual redemption requests, then there is no issue for the bank. It’s possible in theory for a bank to not hold enough gold, just like it’s possible for all businesses to fail to meet their obligations if things go sufficiently wrong, but there is incentive to avoid this result.

To answer some specifics, Kyle’s original inquiry included several questions based on a hypothetical scenario. Let’s consider each.

“…if A deposits $1,000 in the bank, which then lends $800 to B, there’s now $1,800, but with a gold standard there’s still only $1,000.”

In both a gold and fiat standard, the depositor has an account balance that reflects the bank’s obligation to give them $1000. In both standards, the borrower has notes worth $800. If the depositor requested all their currency notes back, the bank would be unable to issue them unless the bank had deposits from other customers, because $800 of A’s deposits is in the hands of B. This is an issue, but it isn’t an issue unique to the commodity system.

“Would A only have access to $200 + whatever B has repaid?”

How much money A has access to depends on the situation. Does the bank have other customers with partial deposits? If not, the bank might have a problem if A wants more than $200. Again, this is true in both the fiat and gold-backed system.

“Where would the extra money for interest paid by B to the bank and by the bank to A come from?”

The interest money paid by B would come from the wealth created by B in the process of paying back the loan. For example, if B started a business and the business sold a product to a customer in exchange for the customer’s gold-backed currency, that’s the money B would use.

“If B skips town, is A out $800?”

Again, that depends on the particulars. A bank could buy deposit insurance or sell bank assets if it wanted to eat the cost of the failed loan (assuming there is no way to cancel those redeemable notes). We could also imagine a bank that tells customers they’re on the hook if borrowers skip town, though I have a tough time imagining many customers would be interested in that arrangement.

You might be tempted to think the theft of the redeemable notes doesn’t hurt the bank because the bank didn’t lose any of the $1,000 in gold. The problem is, when B skips town and spends the notes, the person who accepted the notes has the option of redeeming them. In other words, when the notes are stolen the gold is as good as gone too (again barring some fancy note-canceling technology).

What Makes for Good Commodity Money?

So now we know the difference between commodity money and fiat money. Commodity money should be redeemable for something. But can it be redeemable for anything? We could imagine the commodity that backs a money being anything at all, but in reality certain features of commodities make them better or worse for money.

The economist Carl Menger (1840-1921) provides one of the seminal accounts on how money developed. Menger highlights how the system of barter suffers from several shortfalls including the very important double coincidence of wants (which you can read about here).

As a result of this and other issues, people in barter economies will tend to discover goods which are universally accepted. These universally accepted goods then evolve into being a medium of exchange for most transactions.

So what sorts of qualities do these medium-of-exchange goods have? I don’t claim that this is an exhaustive list, but these goods tend to be: universally enjoyed, portable, durable, divisible, fungible, and recognizable. There’s one final quality that’s hard to put into a single word. Sometimes people say “scarcity”, but I think this is a bad label because it confuses some concepts. I think there are two concepts that this gets at. First, the supply of the good should not be able to grow too quickly. Second, the good should have a high value per unit of weight/space (value density).

Let’s think of some examples to see why some commodities succeed while others fall short. Let’s take copper, for example. Copper has all the first six qualities listed above, however, copper is pretty heavy relative to its value. Copper hovers for around $4 per pound. That means if you wanted to buy a $400,000 house in a copper standard, you’re going to have to somehow transfer ownership of 100,000 pounds of copper. That’s not exactly impossible, but that doesn’t make it ideal. Not only that, the copper supply is so large it lends itself to rapid supply expansion. You’d probably need a rarer and more valuable metal to pair with copper for a working system.

Kyle mentioned a standard with a pretty similar problem to copper—a distilled water standard. Water is similar to copper in a lot of ways as it relates to our qualities. It’s universally enjoyed, portable, durable, divisible, homogeneous, and recognizable. Technically proving it’s distilled maybe makes it a little less recognizable or homogeneous, but the main problem with water (like copper) is it’s pretty cheap per pound (between $1-$4 in stores near me).

The prime rib standard is an interesting proposal because it helps us see some problems. The glaring issue is that prime rib is not very durable. Banks would have to have a lot of freezer space to support that commodity standard.

Admittedly, the list of qualities is not a perfect predictor of what flies as money. We can find historical exceptions to the qualities on the list. But it seems consistent that high-value metals like gold and silver rise to the top on average.

Ask an Economist! Do you have a question about economics? If you’ve ever been confused about economics or economic policy, from inflation to economic growth and everything in between, please send a question to professor Peter Jacobsen at [email protected]. Dr. Jacobsen will read through questions and yours may be selected to be answered in an article or even a FEE video.

Additional Reading:

- In Defense of Fiduciary Media by Drs. George Selgin and Larry White

- On the Origins of Money by Carl Menger

Once the darling of the small banking crisis comeback, New York Community Bancorp has crashed 45% to fresh 30 year lows after The Wall Street Journal reports the bank is seeking to raise equity capital in a bid to shore up confidence in the troubled regional lender.

According to people familiar with the matter, NYCB has dispatched bankers to gauge investors’ interest in buying stock in the company.

There’s no guarantee there will be a deal, or that one would succeed in addressing the bank’s challenges, which as of Wednesday morning had led to a roughly 80% decline in its stock price since January.

As January began, shares of New York Community Bank were selling for more than 10 dollars.

At one point on Wednesday, they were trading for less than 2 dollars.

So why is New York Community Bank in so much trouble?

Well, we are being told it is because “the quality of its commercial real estate loans soured”…

The bank has faced a crisis in recent months after the quality of its commercial real estate loans soured and ratings agencies downgraded its credit status to junk.

Companies are giving up on offices and downtown retail spaces – after Covid normalized working from home and catalyzed the decline of downtown shopping.

That left the owners of commercial buildings unable to pay lenders like NYCB. Some 16 percent of its loans are for commercial real estate acquisition, development and construction.

In other words, New York Community Bank is sitting on a mountain of bad commercial real estate loans.

For a long time, I have been telling my readers that we are going to experience the greatest commercial real estate crisis in U.S. history.

Now, we have reached a stage where nobody can deny what is happening. In fact, billionaire real estate investor Barry Sternlicht says that there will be a trillion dollars in losses on U.S. office properties…

There are growing signs that commercial real estate is in serious trouble.

Barry Sternlicht, a billionaire real estate investor and Starwood Capital’s CEO, recently predicted $1 trillion of losses on office properties alone.

More than $900 billion, or 20%-plus of the total debt owed on US commercial and multi-family real estate, will mature this year, Bloomberg reported this week. Borrowers may have no choice but to refinance at much higher interest rates, or sell their properties at a big discount.

We have never seen anything like this before.

And it is going to have enormous implications for the financial markets.

According to Bloomberg, in recent weeks bond investors “have punished banks with heavy exposure to commercial real estate”…

Bond investors have punished banks with heavy exposure to commercial real estate, potentially adding even more pressure to the lenders’ profits as Wall Street scrambles to assess how widely pain in property debt will spread through the financial system.

Sadly, what we have witnessed so far is just the beginning.

Hundreds of banks all over the nation are drowning in bad commercial real estate loans, and the carnage is going to be immense.

But for the moment, there is some good news.

Somehow, New York Community Bank has been able to locate rubes that are willing to inject a billion dollars into the troubled financial institution…

Shares in New York Community Bank soared this afternoon after the struggling lender announced a $1 billion capital raise and new leadership.

NYCB agreed to a deal with several investment firms in exchange for equity in the regional bank, it announced on Wednesday afternoon.

Those firms include Hudson Bay Capital, Reverence Capital Partners and Liberty Strategic Capital, headed by former US Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin.

Will this be enough to save New York Community Bank?

From a short-term perspective, I think that it will help.

But in the long run I do not think that New York Community Bank will survive.

Of course the same thing could be said about hundreds of other U.S. banks. In fact, as I discussed yesterday, Kevin O’Leary of “Shark Tank” fame is convinced that thousands of U.S. banks will fail during the years ahead.

Meanwhile, trouble signs continue to erupt for the economy as a whole.

According to a survey that was recently conducted by ResumeBuilder, 38 percent of U.S. business leaders expect their companies to conduct layoffs in 2024…

2024 is already looking grim. And it’s only February.

Thirty-eight percent of business leaders surveyed by ResumeBuilder think layoffs are likely at their companies this year, and around half say their companies will implement a hiring freeze. ResumeBuilder talked to around 900 leaders at organizations with more than 10 employees. Half of those surveyed cited concerns about a recession as a reason.

Another major factor: artificial intelligence. Around four in 10 respondents said they’ll conduct layoffs as they replace workers with AI, with Dropbox, Google, and IBM have already announced job cuts for that very reason.

By pumping trillions upon trillions of dollars into the system, those running things were able to keep the economy propped up for a while.

But in the process they created a tremendous amount of inflation, and now the inevitable implosion is coming anyway.

The U.S. economy is in far more trouble than most people realize.

We are going to be entering a period of great economic turmoil just as the most chaotic election season in U.S. history rattles the very foundations of our society.

So I hope that you have been enjoying the “lull” that we have been experiencing during the early portion of this year, because things will certainly get very “interesting” in the months ahead.

Michael’s new book entitled “Chaos” is available in paperback and for the Kindle on Amazon.com, and you can check out his new Substack newsletter right here.

]]>Internal or external auditors occasionally comb through individual loans in a bank’s portfolio and make judgments as to whether those loans are worth what the bank says they are worth due to lower appraised values and other issues either particular to an individual property or the market as a whole. Bankers then, begrudgingly, set aside earnings for potential loan losses.

In the case of the real estate loans at New York Community Bank, loan examiners must have told senior management to increase the bank’s loan loss provision by 790 percent to $552 million. This balance sheet expense drove the fourth-quarter loss and caused the bank to cut its dividend.

“The bank reported a near $2 billion increase in criticized multifamily loans—debt with a probability of default,” wrote Suzannah Cavanagh for the Real Deal. “Of its $37 billion multifamily loan book, which comprises 44 percent of its total portfolio, 8 percent was marked criticized in the quarter.” The bank also reported a $42 million net charge-off—debt unlikely to be paid back—for an office loan on which the borrower stopped paying interest.

The bank’s chief financial officer John Pinto pooh-poohed the loan carnage, saying, “We had higher levels of substandard [loans] throughout the Financial Crisis, throughout the pandemic. The rise in substandard loans does not lead directly to specific losses.”

Hope Springs Eternal

Like the 2008 financial crisis, what happens in the US isn’t staying in the US. Tokyo-based Aozora Bank said losses in its US office’s loan portfolio will likely lead to a net loss for the year ending in March, the Wall Street Journal reports. Also, the private Swiss bank Julius Baer took a roughly $700 million provision on loans made to Austrian property landlord Signa Group. The bank said shutting down the unit was what made the loans, and the chief executive has resigned.

Jay Powell made no mention of the New York Community Bank’s news in his prepared remarks, and reporters didn’t ask him about the bank’s troubles during the Q and A. There were no questions concerning the Bank Term Funding Program that will be sunsetted March 11 despite having risen to record highs. According to the Wall Street Journal’s Andrew Ackerman, the popularity of the program was not because of new stresses on banks. But reportedly, “some banks had recently figured out a way to game the program by pocketing the difference between what they pay to borrow the funds and what they can earn from parking the funds at the central bank as overnight deposits.” On January 31, banks had borrowed more than $165 billion from the facility.

It’s doubtful there are no new stresses on banks. New York Community Bank is not an anomaly.

To that point, real estate investor Barry Sternlicht told a conference crowd…

We have a problem in real estate. In every sector of real estate, not just office, because of the 500 basis point increase in rates that was vertical. The office market has an existential crisis right now . . . it’s a $3 trillion dollar asset class that’s probably worth $1.8 trillion [now]. There’s $1.2 trillion of losses spread somewhere, and nobody knows exactly where it all is.

Sternlicht mentioned a project in New York that was purchased for $200 million that he thought was now worth just $30 million, encumbered by a $100 million loan.

Harold Bordwin, a principal at Keen-Summit Capital Partners LLC in New York, which specializes in renegotiating distressed properties, told Bloomberg, “Banks’ balance sheets aren’t accounting for the fact that there’s lots of real estate on there that’s not going to pay off at maturity.”

Bordwin went on to say, “Banks—community banks, regional banks—have been really slow to mark things to market because they didn’t have to, they were holding them to maturity. They are playing games with what is the real value of these assets” (emphasis added).

“The percentage of loans that banks have so far been reported as delinquent are a drop in the bucket compared to the defaults that will occur throughout 2024 and 2025,” David Aviram, principal at Maverick Real Estate Partners told Bloomberg. “Banks remain exposed to these significant risks, and the potential decline in interest rates in the next year won’t solve bank problems.”

The plan for the Bank Term Funding Program was hatched in haste over a weekend in March of last year in the wake of the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failures (Signature’s assets were purchased by New York Community Bank). To hide their embarrassment over banks using the facility for risk-free interest rate arbitrage, they say they are shutting the program down because there is no stress in the banking system.

There is stress aplenty in the banking world. As Murray Rothbard wrote in The Mystery of Banking, “Fractional reserve bank credit expansion is always shaky, for the more extensive its inflationary creation of new money, the more likely it will be to suffer contraction and subsequent deflation.”

While bankers and regulators have their heads in the sand, the contraction has already begun.

About the Author

Douglas French is President Emeritus of the Mises Institute, author of Early Speculative Bubbles & Increases in the Money Supply, and author of Walk Away: The Rise and Fall of the Home-Ownership Myth. He received his master’s degree in economics from UNLV, studying under both Professor Murray Rothbard and Professor Hans-Hermann Hoppe. His website is DouglasInVegas.com.

]]>America’s sixth-largest bank, PNC, has confirmed the closure of 19 more branches nationwide, following a staggering 203 branch closures earlier this year. This decision, aligning with the bank’s shift towards digital banking, is raising concerns among customers who prefer traditional banking methods.

Scheduled for February 2024, the closures will primarily impact Pennsylvania, where the majority of branches marked for closure are located. However, several branches in other states, including Illinois, Texas, Alabama, New Jersey, Ohio, Florida, and Indiana, will also be shutting their doors, leaving customers in these regions with limited access to in-person banking services, The Sun reported.

Of course PNC has lots of company.

During that exact same week, several other prominent banks made similar moves…

JPMorgan Chase followed closely with 18 filings—three in Ohio, two each in Connecticut and South Carolina, and one each in 11 states, including New York, Illinois, Florida, and Massachusetts.

Citizens Bank came in third with eight branch closure filings—six in New York, and one each in Massachusetts and Delaware. Minneapolis-based U.S. Bank filed for seven closures—three in Tennessee and one each in Missouri, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Illinois.

Bank of America made five filings—two in New York and one each in Texas, Massachusetts, and California.

Citibank filed for two branch closures, and Sterling, Bremer, First National Bank of Hughes Springs, Windsor FS&LA, and Aroostook County FS&LA made one filing each.

Altogether, banks filed to shut down 64 branches.

Read that last sentence again.

In just one week, U.S. banks decided to shut down a total of 64 branches. That is stunning.

What we are witnessing right now is a tsunami of branch closures.

Unfortunately, even more trouble is coming for our banks because the real estate industry is a total mess right now.

Existing home sales have fallen to depressingly low levels, and we just learned that new home sales in the U.S. dropped 5.6 percent last month…

New home sales in the United States fell in October as typical mortgage rates reached their highest levels this year.

Sales of newly constructed homes fell 5.6% in October to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 679,000, from a revised rate of 719,000 in September, according to a joint report from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Census Bureau.

Prices for new homes are falling as well…

So the median price of new single-family houses sold in October fell by 3.1% from September, to $409,300 (red line), the lowest since August 2021, down by 17.6% from a year ago, which had been the peak, according to data from the Census Bureau today. The three-month moving average is down by nearly 12% from its peak in December last year (green).

These are contract prices and do not include the costs of mortgage-rate buydowns and other incentives such as free upgrades. But they do reflect the lower price points due to smaller footprints and the “de-amenitizing.”

Meanwhile, the commercial real estate crisis just continues to intensify.

Just check out these new numbers that were released several days ago by Trepp…

The volume of CMBS loans that are classified as delinquent increased by 49.4% during the 10 months through October to $27.91 billion. That volume amounts to 5.07% of the $601.98 billion universe tracked by Trepp. In contrast, delinquencies at the end of last year amounted to 3.03% of the $616.15 billion universe then extant.

Wow.

It turns out that office buildings are the primary reason why delinquencies are rising at such an astounding pace…

The driver of the increase was the office sector, which had a 261% increase in delinquency volumes over the 10-month period through October. A total of 199 loans with a balance of $9.59 billion, or 5.91% of all CMBS office loans were at least 30 days late with their payments, as of the end of October. At the end of last year, 115 loans with a balance of $2.65 billion, or 1.63% of office loans, were delinquent.

The sector’s prospects are unlikely to improve as office occupancy rates have declined in most of the country’s major markets. That’s been driven by a substantial pullback in demand from office-using tenants.

All of this reminds me so much of what we witnessed in 2008.

When the real estate industry falls on hard times, a financial crisis is usually right around the corner. Needless to say, it isn’t just U.S. banks that are in trouble right now.

Major banks all over the globe are getting hit really hard, and that includes Metro Bank in the UK…

Metro Bank shareholders have backed a multi-million pound rescue deal aimed at securing the bank’s future.

The vote was on a package the bank agreed last month to raise extra funds from investors and refinance debt. Metro’s share price had plunged in September following reports it needed to raise cash to shore up its finances.

In the days ahead, we are going to hear about a lot more banks that need to “shore up” their finances. And it is inevitable that more banks will fail.

A number of people have asked me questions about their banks lately, and I have told them the same thing that I tell everyone. It is never wise to put all of your eggs in one basket.

We are moving into a period of time that is going to be extremely chaotic, and so you don’t want to have all of your assets in a single place.

What we have seen so far is just the beginning. Our banks are going to get into even deeper trouble during the days ahead, and that is really bad news for all of us.

Michael’s new book entitled “Chaos” is now available in paperback and for the Kindle on Amazon.com, and you can check out his new Substack newsletter right here.

]]>In yet another display of America’s cracking financial system – when will the thing finally die already? – customers who use direct deposit to transfer their earnings from their employers to themselves say the funds are not posting, which the establishment is blaming on “human error.”

We are told that the Automated Clearing House (ACH) payments system is experiencing “problems” that are causing major headaches for not just consumers but also their employers.

“The Federal Reserve encourages banks to work quickly to resolve issues for customers experiencing delays in receiving direct deposit payments as a result of operational issues at a private sector payments provider,” announced a spokesperson from the Fed.

(Related: How can this all be happening when fake president Joe Biden told Americans back in March that “the banking system is safe?”)

America’s banks promise that customer funds are “secure”

One thing the Fed is signaling to the usury masters is that they need to at least waive all overdraft and late fees associated with these issues, which JPMorgan Chase has said it will do.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau likewise indicated that consumers “should not be penalized” with fees or whatever else for issues that stem from America’s highly corrupt financial system, which is more of a Ponzi scheme for the rich than anything else.

“The Federal Reserve’s payments services are separate and functioned normally,” claimed a Fed spokesperson in a follow-up statement.

According to the nation’s banks, all customer funds are “secure,” even if the system is showing signs of imploding in on itself at any moment.

As for payments that were sent but did not go through last week, banks are now telling customers that everything is just fine because the process “can take time.”

The Clearing House, a private group that operates the ACH, claims it is working both with banks and the Fed to “resolve this issue as quickly as possible,” though it would not share anything further with the media.

According to a spokesman from the private Clearing House, all of this began as a “processing error” when some ACH payment instructions were sent to financial institutions with account numbers and customer names “masked.”

“That missing data meant that some ACH payments were delayed,” reported one media source about the matter.

Less than one percent of the daily ACH volume in the United States was affected by this problem, according to the Clearing House.

In the month of September, the ACH Network processed an average of $330 billion per day, according to Nacha, a nonprofit organization that governs the network.

Among the banks where customers reported ACH problems are most of the usual suspects: Bank of America, Chase, Wells Fargo, U.S. Bank and Truist.

The latest reports suggest that hundreds of thousands of payments have been delayed because of this “processing error.”

“In many cases,” the Clearing House admitted, these transfers will continue to be delayed.

In some states, these delays are actually illegal, such as in Texas where one person reported the matter to Attorney General Ken Paxton, noting that Bank of America, in his case, “is non-compliant with regulations and it’s impacting Texas customers.”

“Some deposits from 11/3 may be temporarily delayed due to an issue impacting multiple financial institutions,” reads a prompt from BofA about the deposit delays at that bank.

“Your accounts remain secure, and your balance will be updated as soon as the deposit is received. You do not need to take any action.”

Fiat “money” is an illusion. Learn more at Collapse.news.

Sources for this article include:

]]>For example, the percentage of subprime borrowers that are at least 60 days behind on their auto loans reached 6.11 percent last month.

That figure is the highest ever recorded…

The percent of subprime auto borrowers at least 60 days past due on their loans rose to 6.11% in September, the highest in data going back to 1994, according to Fitch Ratings.

“The subprime borrower is getting squeezed,” said Margaret Rowe, senior director with Fitch.

Let this sink in for a moment.

We never saw a number this high during the Great Recession.

And we never saw a number this high during the COVID pandemic.

So this is really bad.

Credit card delinquency rates at small banks have also hit an all-time record high…

Credit Card Delinquency rates at small banks have reached 7.51%, the highest level ever recorded

Once again, we never saw a number this high during the Great Recession.

And we never saw a number this high during the COVID pandemic.

Needless to say, it isn’t the wealthy that are getting behind on their credit card payments.

Instead, it is ordinary Americans that are deeply struggling to pay the bills in this harsh economic environment. Alarmingly, early-stage mortgage delinquencies are also spiking…

Meanwhile, early-stage delinquencies (30 and 60 days past due) continued to increase. In September, 48,800 (+5.1%) additional borrowers were 30-days late on their mortgage payments, while 8,700 (+3%) were 60-days late on their mortgage payments. These rates have been going up for the past four months and six months, respectively.

And foreclosures have started to jump at a pace that is absolutely breathtaking…

Home foreclosures are on the rise as Americans continue to grapple with the ongoing cost-of-living crisis.

That is according to a new report published by real estate data provider ATTOM, which found that foreclosure filings – which includes default notices, scheduled auctions and bank repossessions – surged 28% in the third quarter to 124,539.

Foreclosures are up 34% from the same time one year ago.

Just like we witnessed in 2008 and 2009, millions upon millions of Americans have gotten way too overextended.

Even though everyone knew that the cost of living was rising much faster than paychecks were, a lot of people out there just kept spending like they always had been.

They thought that things would eventually work out okay in the long run, but instead they just kept getting deeper and deeper into debt. Now a day of reckoning has arrived, and there are many that simply cannot keep up with all of their payments. And many are falling out of the middle class altogether.

In all my years of writing, I have never seen poverty increase in the U.S. as fast as it is rising right now. Recently, we learned that the percentage of Californians living in poverty jumped from 11 percent in 2021 to 16.4 percent last year…

Poverty has increased dramatically in California and the nation, a surge that new studies attribute to the expiration of pandemic-era federal relief programs such as the expanded Child Tax Credit.

The spike has been particularly steep among Black and Latino Californians and children across all ethnicities.

Researchers found 16.4% of Californians were living in poverty last year, up from 11% in 2021. The rate of child poverty more than doubled last year.

What will the final number for 2023 be? Will it be above 20 percent? The economy is moving in the wrong direction very rapidly now, and the war in the Middle East hasn’t even fully erupted yet. So what in the world will conditions look like once that happens?

Our economic prosperity is completely and utterly dependent on cheap energy. Without it, everything will change.

Once the flow of Middle Eastern oil stops due to the war, the price of oil is going to go completely nuts. And once that happens, a nightmare scenario could quickly unfold.

In a recent article, Tuomas Malinen detailed what he thinks might happen…

- The conflict escalates into a regional war with the U.S. becoming directly involved.

- OPEC responds with an oil embargo.

- Iran closes the strait of Hormuz.

- The price of oil reaches $300/barrel.

- Europe succumbs into a full-blown energy crisis due to LNG shortage.

- Massive spike in energy prices reinvigorates inflation with central banks responding accordingly.

- Financial markets and the global banking sector collapse.

- Debt crisis engulfs the U.S. forcing the Federal Reserve to enact yet another financial market bailout.

- Petrodollar trade collapses.

- Hyperinflation emerges.

I don’t think that he is too far off the mark. We were already facing a major crisis even without the war in the Middle East.

As I discussed the other day, U.S. banks are closing hundreds of branches and are laying off thousands of workers. And the truth is that the banks are the beating heart of our entire financial system.

We are so close to a full-blown economic meltdown. The only thing that could really save us now is if peace broke out in the Middle East.

Unfortunately, this is not going to be a time of peace. This is going to be a time of war.

So that means that extremely harsh economic conditions are ahead of us, and most Americans are completely and utterly unprepared for such a reality.

Michael’s new book entitled “End Times” is now available in paperback and for the Kindle on Amazon.com, and you can check out his new Substack newsletter right here.

]]>Current problems in the banking system are reviving uncomfortable memories of the global financial crisis, and the risks of widespread bank failures are higher than at any other period. That’s why Wall Street analysts are pointing the finger of blame to regulators once again.

In a recent analysis published on Parade.com, financial experts Pam and Russ Martens exposed that U.S. regulators and the central bank are withholding important information about the real financial condition of several large financial institutions for over a year and a half not to alarm the public, and spark more bank runs and failures.

They discovered that on March 30, 2022, the Fed reported that unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities at the 25 largest U.S. banks were approaching the levels they had reached during the financial crisis in 2008. On that same day, the central bank stopped reporting data about the bank’s unrealized gains and losses on securities. It can’t be just a coincidence that this data series was halted right after the Fed started raising rates on March 17, 2022.

That made things exponentially worse for U.S. banks because they had loaded up on low-interest-rate Treasury securities and federal agency Mortgage-Backed Securities. They did so because their deposit balances had swollen to a historic level as a result of the trillions in stimulus payments that the federal government directly deposited into depositor accounts at banks during the health crisis.

Back then, the pandemic led to mass business closings which negatively impacted business loan demand and made banks turn to government-backed bonds as a safe place to park the trillions of dollars in extra deposits. But these lost a good deal of value as interest rates were increased. Lenders ended up with paper losses, leaving investors unimpressed.

At this moment, nearly 200 banks are in danger of suffering the same woes as Silicon Valley Bank. If just 10 small and mid-sized banks fail in the months ahead, that could trigger a cascade of failures and that would bring down larger banks as well. In turn, a major credit crunch would make it impossible for businesses and consumers to access credit. In fact, a credit crisis is already in motion.

Last week, bank credit fell further on a year-over-year basis. Meanwhile, corporate and personal bankruptcies are already spiking, and so are consumer debt delinquencies.

Many Americans already report that their access to credit has deteriorated in 2023, and they shouldn’t expect a reversal any time soon. On top of all that, more bank failures would certainly cause more bank runs on these vulnerable financial institutions, damaging confidence in the banking system and causing a broader panic. Ultimately, when lending dries up, that will weigh on the value of stocks, real estate, and other assets, and crimp overall demand — a recipe for a disastrous recession and the worst financial crisis in our lifetimes, just as the experts have been warning all along.

]]>Now it’s 2023 and Scott Hildenbrand, the chief balance sheet strategist at Piper Sandler, tells Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway on Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast,

And so if you had told me, Joe, or Tracy five years ago, you had me on here and you said, “There’s a bank and all they’re going to do is buy treasuries and all of their deposits are in checking accounts. And by the way, they’re going to fail,” I would’ve laughed at both of you. I wouldn’t have come back. I would have been like, “You all are crazy.”

Rothbard wasn’t so crazy after all.

Hildenbrand was on Odd Lots to explain how tough things are for small community banks. Jamie Dimon’s JPMorgan has all sorts of revenue streams, but the community bank has to take deposits, lend them out, and live on the difference in interest rates. Silicon Valley Bank was “not like the WAMU days or not It’s a Wonderful Life. It was three hours and $42 billion. That’s what happened.”

Hildenbrand made a point that’s never mentioned: banks don’t make money lending; banks make money because “they don’t pay at market rates on the deposit side.” Banks don’t typically pay anything on checking account deposits. That is where banks earn their spread. It didn’t matter because it used to be that bank customers were very loyal. Bankers could count on that checking account money staying in place. Not so much anymore. Money moves fast for two reasons according to Hildenbrand: technology and demographics.

Back in the day customers were very loyal but had very little trust. Today, “there’s a ton of trust. They’ll move money around on phones. They don’t even know the name of the bank they’re banking at,” Hildenbrand said. “They’ll move it so quickly. But there’s very little loyalty. And therein lies the difference in why we’re struggling with how to determine how to manage and hedge a balance sheet from a deposit perspective.”

Bankers didn’t realize the effects on deposits of technology, social media, and demographic changes from a liquidity perspective in a higher rate environment. A decade or two ago a community bank had almost half of its deposits in CDs. And, as Hildebrand says, “That gave banks time.” Now bankers won’t get that kind of time due to demographics.

Hildebrand interviews lots of young people for Piper Sandler who come to New York to learn about community banking. As smart as these young people are, he quipped, “I always have a question they can’t answer. Do you know what a CD is? And they’ve never heard of it, whether it was banking or music.” A certificate of deposit (CD) is a savings product that earns interest on a lump sum for a fixed period of time. The money must remain untouched for the entirety of their term or penalties or lost interest may apply. As an incentive for lost liquidity, CDs usually have higher interest rates than savings accounts.

Nowadays, “people want CD rates with money market flexibility and operational flexibility,” Hildebrand told Alloway and Weisenthal. “We have no contractual liabilities on most bank balance sheets anymore.”

Since the spring spate of regional bank failures, only one bank has failed—the $139 million Heartland Tri-State Bank in Elkhart, Kansas. But more failures and consolidations are coming. Hildebrand said half the banks in the country are trading at less than book value (assets-liabilities/shares). That means investors don’t trust the loan and investment values on bank balance sheets. He believes from the four thousand banks the United States has now, the number of banks will shrink to two hundred over the next ten to fifteen years.

Rothbard wrote in Making Economic Sense, “The banking system, in short, is a house of cards.” The house of fraud will have fewer cards going forward.

Sound off about this article on our Economic Collapse Substack.

About the Author

Douglas French is President Emeritus of the Mises Institute, author of Early Speculative Bubbles & Increases in the Money Supply, and author of Walk Away: The Rise and Fall of the Home-Ownership Myth. He received his master’s degree in economics from UNLV, studying under both Professor Murray Rothbard and Professor Hans-Hermann Hoppe. Article cross-posted from Mises.

]]>To answer that question, we must enter the magical kingdom of “fractional-reserve banking,” where deposits are turned into loans, loans are turned into money, and so on. For every old dollar that goes in, nine new dollars come out, created with the stroke of a pen or the click of a mouse. As you may be aware, general deposits are loans by the bank depositor to the bank. However, banks can spin new loans out of old loans, creating a wheel of fortune by lending the same dollar to nine different customers—a feat that, to the uninitiated, is equally quite amazing and frightening!

This financial alchemy is perfectly legal and is in fact carried out with the aid and assistance of central banks everywhere, including our own Federal Reserve. If this wheel of fortune should hit a bump in the road and suddenly fall off its axle, causing the bank to crash, don’t worry because a central bank can do what no one else can legally do: counterfeit new money to set things right, a feat that “all the king’s horses and all the king’s men” cannot do!

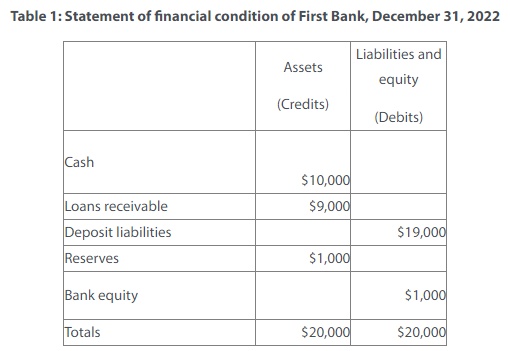

Let’s take a closer look at how fractional-reserve banking works. Customer A deposits $10,000 in a checking account at First Bank. First Bank records the cash in its books and credits customer A’s account. The cash is an asset of the bank (a credit), which is offset by the liability to customer A (a debit). First Bank now has cash to lend, subject to government reserve requirements. Reserve requirements, which are established by the Fed, specify the amount (expressed as a percentage of deposits) that a lending institution must hold in reserve, either as vault cash or on deposit with a Federal Reserve bank, in order to guarantee payment of customers’ deposits. The reserve requirement for “reservable” deposits greater than $36.1 million (as of January 3, 2023) at any lending institution has been traditionally 10 percent. As a result, First Bank is free to lend $9,000 of the deposited money, keeping $1,000 in reserve.

Customer B comes into First Bank seeking a car loan. First Bank agrees to lend customer B $9,000. First Bank credits customer B’s checking account for $9,000 and debits an asset account called “loans receivable.” As you will recall, bank loans to customers are “investments” and, therefore, are assets—not liabilities.

At the completion of these two transactions, First Bank’s statement of financial condition would look like this (for simplicity, I have assumed no other transactions).

Notice that the bank has deposit liabilities of $19,000 and cash on hand of $10,000. Let’s assume that the loan to customer B is for three years, payable with interest in monthly installments. The demand deposits (checking account balances) include the original deposit of $10,000 from customer A plus the proceeds of the loan to customer B of $9,000. Presumably, customer B will spend the loan money on a car in the next few days. Where did the loan money credited to customer B’s checking account come from? Out of thin air!

The wheel turns again when the car dealer deposits the $9,000 proceeds in his bank, Second Bank. Now Second Bank, like First Bank, is free to make loans, subject to the 10 percent reserve requirement. When the wheel finally stops turning, loans of $90,000 have been created on a cash base of just $10,000. As we have seen, that cash is itself a chimera—nothing more than debt wrapped inside more debt.

The table above demonstrates that banks can expand the money supply by a factor of ten when the reserve requirement is 10 percent. Historically, the United States reserve requirement has been 10 percent on transaction deposits, such as checking and negotiable order of withdrawal accounts (M1) deposits, and 0 percent on time deposits, such as deposits into savings accounts and certificates of deposit. The 0 percent reserve requirement on time deposits enables banks to expand the money supply by more than a factor of ten.

Some would argue that banks are not really “insolvent,” just at times illiquid—not always having ready cash when needed. However, that’s true only if we consider just one or a few banks at a time. Any bank having a temporary shortage of cash could always borrow the needed funds to make up for the temporary cash shortage. The problem, however, is that all banks are illiquid and, when pricked by some general financial shock, can easily slip into insolvency.

When the reserve ratio is 10 percent, total deposits are reduced by ten dollars for every dollar withdrawn from the banking system. Banks then have to call in loans or sell securities to cover their depositor’s demands for money. This “liquidity crisis” is the reason behind most financial “panics,” bank runs, and similar economic disturbances. It’s “debt on the way down,” but this time on a grand scale!

Effective March 26, 2020, the Federal Reserve reduced bank reserve requirements, get this, to zero! Even prior to this change, reserve requirements only applied to transaction accounts, nonpersonal time deposits, and Eurocurrency liabilities. Everything else was “jokers are wild.” Thus, banks could create as much funny money as the traffic would bear. When reserve requirements are zero, the ability to create money is infinite!

The Fed’s money manipulation is the root cause of our economic problems. Bubbles in housing prices, United States Treasury notes and bonds, and cryptocurrencies—to give but a few examples—and the recent failures of the Silicon Valley, Republic, and Signature banks can all be traced to our monetary policies.

The fundamental issue for most banks is that they are forced to invest “long” but borrow “short,” something no prudent finance manager would ever do. Checking and other demand deposits are short-term liabilities of the bank. Bank loans, such as car loans, are intermediate-term investments. Mortgage loans are long-term investments. Banks also invest in government securities to balance their investment loan portfolio. Investing “long,” however, subjects the bank to interest-rate risks because the value of their investment loan portfolio is inversely related to changes in interest rates. A thirty-year mortgage loan yielding 2 percent is only worth a fraction of a similar loan yielding 6 percent. To be more precise, a $100,000 investment in such an instrument would be worth only $44,280 if interest rates were to rise to 6 percent. If interest rates rise to 8 percent, the value would fall to $31,768, according to the bond price calculator.

Therein lies the trap that Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) fell into—with disastrous results. It’s the trap set by the very nature of fractional-reserve banking:

Over a period of just two days in March 2023, the bank went from solvent to broke as depositors rushed to SVB to withdraw their funds, resulting in federal regulators closing the bank for good on March 10, 2023.

SVB’s collapse marked the second largest bank failure in U.S. history after Washington Mutual’s in 2008.

That money created out of thin air should one day evaporate before our eyes should surprise no one, except perhaps Paul Krugman and his fellow court jesters at the New York Times. The endless cycles of boom and bust are a direct result of government manipulation of the money supply. It’s really that profound and that simple.

About the Author

Stephen Apolito is a CPA living in Bronxville, New York. A veteran of the US Air Force, Apolito is a graduate of Washington and Lee University and has taught in the New York City public schools.

Article cross-posted from Mises.

]]>