Can you explain how commodity-backed currencies, like the gold standard, work with regards to saving and lending? As I understand it, with fiat money, if A deposits $1,000 in the bank, which then lends $800 to B, there’s now $1,800, but with a gold standard there’s still only $1,000. Would A only have access to $200 + whatever B has repaid? Where would the extra money for interest paid by B to the bank and by the bank to A come from? If B skips town, is A out $800?

Also, can you explain what would make a good commodity to back a currency? Would a plutonium standard, a distilled water standard, or prime rib standard work as well as a gold standard or silver standard?

To tackle the first question, we need to highlight the differences between a currency system and a banking system. Let’s start there.

Commodity vs. Fiat Money

So does commodity money, like a gold-standard, conflict with how banks operate today? Not really. To understand why, we need to get to the fundamental difference between commodity money and fiat money—redeemability.

A commodity money is redeemable for some quantity of a physical commodity. For example, we can imagine a paper currency which could be redeemed for one ounce of silver, gold, plutonium, or prime rib. If you can, in principle, take the note to a bank or government office (depending upon the specifics of the system) and have it redeemed for gold, the currency is a gold-backed currency.

Fiat currency, on the other hand, is only redeemable in itself. In other words, if you take your currency to a bank or government office in a fiat system to redeem it, they are going to hand you back different fiat currency. If you redeem your five dollar bill, the only thing you’re promised is five slightly different colored bills with Washington’s face rather than Lincoln’s.

This is the difference between fiat and commodity systems.

So, is a commodity-based monetary system compatible with banking as we know it today? Sure. Let’s run through an example to see why.

Let’s say you deposit $1,000 worth of gold at a bank. In exchange you receive $1,000 of redeemable gold-backed notes, which you can use to purchase products. If the notes are transferred, the person who receives them can redeem them for their portion of the gold. The bank has the gold it would be required to give for redemption.

In some historical government money systems, the government offers the right to gold redemption rather than the private bank, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imagine banks or private gold redemption businesses taking this on. For our purposes, we’ll just assume that the banks store gold for redemption and allow customers to save their notes. This system is maybe overly simple compared to reality, but it makes our example a bit easier.

You decide that instead of spending your gold notes, you’d prefer to save them, and you deposit the notes in the bank as well.

Someone comes along and borrows notes from the bank. The bank gives the borrower $800 worth of gold-backed currency from the $1,000 you deposited in the bank. So now, your bank account balance is $1,000 (recorded on the bank’s ledger), and the borrower has $800 in physical cash. This sort of banking system where the bank only keeps a fraction of the money deposited and lends out the rest is known as fractional reserve banking.

At this point, you may have noticed the problem that Kyle noticed. The bank essentially created new money when it loaned your money out to someone else. There is now $1,800 worth of promises to redeem currency in gold out there, but the amount of gold hasn’t changed. There’s still only $1,000 worth of gold. So is this an issue?

Well, it’s only an issue for the bank if everyone decides to redeem their currency for gold at the exact same time. In that case, the bank would be unable to meet its obligations, and it would go under unless something changed.

You might take this possibility as evidence that commodity-backed money is incompatible with fractional reserve banking. There’s two reasons why this isn’t necessarily the case.

First of all, this potential problem is not unique to commodity money. If banks hold fractional reserves in a fiat money system the same issue still applies. If every depositor runs to the bank and demands their fiat money, a bank will be unable to fulfill that obligation if they only kept a fraction of the fiat and lent out the rest.

In other words, this risk associated with fractional reserve banking is not specific to a commodity or fiat system. The risk of too many customers trying to secure funds exists in both systems. The type of money (commodity or fiat) is a separate question from the type of banking system (fractional or full reserves).

Second of all, as long as the bank keeps enough gold on hand to meet the actual redemption requests, then there is no issue for the bank. It’s possible in theory for a bank to not hold enough gold, just like it’s possible for all businesses to fail to meet their obligations if things go sufficiently wrong, but there is incentive to avoid this result.

To answer some specifics, Kyle’s original inquiry included several questions based on a hypothetical scenario. Let’s consider each.

“…if A deposits $1,000 in the bank, which then lends $800 to B, there’s now $1,800, but with a gold standard there’s still only $1,000.”

In both a gold and fiat standard, the depositor has an account balance that reflects the bank’s obligation to give them $1000. In both standards, the borrower has notes worth $800. If the depositor requested all their currency notes back, the bank would be unable to issue them unless the bank had deposits from other customers, because $800 of A’s deposits is in the hands of B. This is an issue, but it isn’t an issue unique to the commodity system.

“Would A only have access to $200 + whatever B has repaid?”

How much money A has access to depends on the situation. Does the bank have other customers with partial deposits? If not, the bank might have a problem if A wants more than $200. Again, this is true in both the fiat and gold-backed system.

“Where would the extra money for interest paid by B to the bank and by the bank to A come from?”

The interest money paid by B would come from the wealth created by B in the process of paying back the loan. For example, if B started a business and the business sold a product to a customer in exchange for the customer’s gold-backed currency, that’s the money B would use.

“If B skips town, is A out $800?”

Again, that depends on the particulars. A bank could buy deposit insurance or sell bank assets if it wanted to eat the cost of the failed loan (assuming there is no way to cancel those redeemable notes). We could also imagine a bank that tells customers they’re on the hook if borrowers skip town, though I have a tough time imagining many customers would be interested in that arrangement.

You might be tempted to think the theft of the redeemable notes doesn’t hurt the bank because the bank didn’t lose any of the $1,000 in gold. The problem is, when B skips town and spends the notes, the person who accepted the notes has the option of redeeming them. In other words, when the notes are stolen the gold is as good as gone too (again barring some fancy note-canceling technology).

What Makes for Good Commodity Money?

So now we know the difference between commodity money and fiat money. Commodity money should be redeemable for something. But can it be redeemable for anything? We could imagine the commodity that backs a money being anything at all, but in reality certain features of commodities make them better or worse for money.

The economist Carl Menger (1840-1921) provides one of the seminal accounts on how money developed. Menger highlights how the system of barter suffers from several shortfalls including the very important double coincidence of wants (which you can read about here).

As a result of this and other issues, people in barter economies will tend to discover goods which are universally accepted. These universally accepted goods then evolve into being a medium of exchange for most transactions.

So what sorts of qualities do these medium-of-exchange goods have? I don’t claim that this is an exhaustive list, but these goods tend to be: universally enjoyed, portable, durable, divisible, fungible, and recognizable. There’s one final quality that’s hard to put into a single word. Sometimes people say “scarcity”, but I think this is a bad label because it confuses some concepts. I think there are two concepts that this gets at. First, the supply of the good should not be able to grow too quickly. Second, the good should have a high value per unit of weight/space (value density).

Let’s think of some examples to see why some commodities succeed while others fall short. Let’s take copper, for example. Copper has all the first six qualities listed above, however, copper is pretty heavy relative to its value. Copper hovers for around $4 per pound. That means if you wanted to buy a $400,000 house in a copper standard, you’re going to have to somehow transfer ownership of 100,000 pounds of copper. That’s not exactly impossible, but that doesn’t make it ideal. Not only that, the copper supply is so large it lends itself to rapid supply expansion. You’d probably need a rarer and more valuable metal to pair with copper for a working system.

Kyle mentioned a standard with a pretty similar problem to copper—a distilled water standard. Water is similar to copper in a lot of ways as it relates to our qualities. It’s universally enjoyed, portable, durable, divisible, homogeneous, and recognizable. Technically proving it’s distilled maybe makes it a little less recognizable or homogeneous, but the main problem with water (like copper) is it’s pretty cheap per pound (between $1-$4 in stores near me).

The prime rib standard is an interesting proposal because it helps us see some problems. The glaring issue is that prime rib is not very durable. Banks would have to have a lot of freezer space to support that commodity standard.

Admittedly, the list of qualities is not a perfect predictor of what flies as money. We can find historical exceptions to the qualities on the list. But it seems consistent that high-value metals like gold and silver rise to the top on average.

Ask an Economist! Do you have a question about economics? If you’ve ever been confused about economics or economic policy, from inflation to economic growth and everything in between, please send a question to professor Peter Jacobsen at [email protected]. Dr. Jacobsen will read through questions and yours may be selected to be answered in an article or even a FEE video.

Additional Reading:

- In Defense of Fiduciary Media by Drs. George Selgin and Larry White

- On the Origins of Money by Carl Menger

Suppose you lived in the eighteenth century and had a hundred ounces of gold. It’s heavy, and you do not live in a safe neighborhood, so you decide to bring it to a goldsmith for safekeeping. In exchange for this gold, the goldsmith gives you ten tickets on which are clearly marked as claims against a total of ten ounces. Now, gold is heavy and burdensome to carry, so in a short period of time, those claims will start circulating in place of gold. This is the creation of near monies. This doesn’t mean you have given up your ownership claims on gold but have instead used a simpler way of transferring ownership on this gold.

Of course, the gold now just sits in the vault, and no one usually comes to get some of it or even checks that it is still there. Quickly, the goldsmith realizes there is an easy, fraudulent way to get rich: just lend out the gold to someone else by creating another ten tickets. Since the tickets are rarely redeemed for actual gold, the goldsmith figures he can run this scam for a very long time. Of course, it is not his gold, but since it is in his vault, he can act as though it is his money to use.

This is fractional reserve banking with a reserve of 50 percent. This is also how the banking system can create money out of thin air, or basically counterfeit money, and steal the purchasing power from others without having to produce real goods and services. On March 26, 2020, the United States central bank reduced reserve requirements for US banks to 0 percent from 10 percent in reaction to the economic effects of the covid pandemic.

Now the goldsmith, or what we will now call a bank, is limited in the amount of fraud or counterfeiting it can commit. There is a hundred ounces of gold and claims on two hundred ounces of gold. The bank must keep a certain amount of gold in its vaults since depositors on occasion will exchange tickets for gold. Another constraint is that depositors, if they get suspicious that there are more claims than available gold, may run to the bank demanding to redeem their “on demand” claims into gold.

This run, really, only reflects the totally fraudulent nature of banking. Banking holidays, which were implemented in the ’30s, or capital controls, which were implemented recently in Cyprus, are actions to benefit the fraudster (the banks) instead of the victim (the depositors). Of course, the European Central Bank supported these actions by Cyprus. The world has been turned on its head.

Suppose you are the goldsmith, and your rich uncle promises to lend you as much gold as you need if you happen to run out (the lender of last resort function of the central bank). Are you likely to commit more fraud? Suppose this rich uncle tells you that if things go bad, he will make sure everyone gets their gold back (deposit insurance). Again, are you likely to commit fraud? Since you have no skin in the game, are you likely to take even more risks, for higher returns, in your lending activities?

Austrian economists have a hard time explaining why fractional reserve banking is fraudulent. The standard response from the average Joe is that “everyone knows that the bank loans out your money.” Or they will say that “all banks in the US include a clause in the depositor’s contract that specifically says that the relationship between the depositor and the bank is exclusively one of creditor and debtor.”

Suppose the bank takes your money and loses it all. How does the bank satisfy your expectation that the money is there on demand to pay your rent and electricity bills? It’s simple. They take the money from someone else. If the bank had told you that the money is unfortunately lost, there would be no fraud (if you had signed a clear statement on the use of your funds). The fraud occurs the minute the bank takes someone else’s money. The victims of the fraud are the other depositors.

The bank essentially runs a Ponzi-like scheme (a fraudulent activity) that can continue for a very, very long time, but it is no less a fraudulent activity and should be treated as such. Although you and the bank may be aware of what is going on, it still should be treated as fraud. The fact that you are aware, or even unaware, of the Ponzi-like scheme does not diminish the fraud. Government deposit insurance just shifts the ultimate cost of the fraud to other depositors, taxpayers, or anyone using currency to conduct transactions.

Why is counterfeiting illegal? The counterfeiter is happy since he gets real goods and services, and the store owner is happy since he made a sale and can also get more real goods and services if he spends the money quickly before prices go up. So where is the problem? The transaction has been beneficial to both. It is illegal because of third-party effects.

The counterfeiter takes from the economic pie but does not contribute to the economic pie. He has basically stolen real goods and services by reducing the purchasing power of the money in everyone else’s pockets. When the fractional reserve banking system creates money out of thin air, it is also a form of counterfeiting and has undesirable third-party effects. Economists know that it is the rapid expansion of money and credit, unjustified by the growth of slow-moving savings, that has created the booms and busts of the last two centuries, and the hardships that have gone along with them.

Eliminate fractional reserve banking and you eliminate booms and busts. Unable to create money out of thin air, banking would now just be another sector without the ability to sink the entire world economy.

We need to start a serious discussion about ending fractional reserve banking, and central banking at the same time. Our current banking system is not free market capitalism. Banking in its current form should be outlawed because it is both fraud and theft.

]]>To answer that question, we must enter the magical kingdom of “fractional-reserve banking,” where deposits are turned into loans, loans are turned into money, and so on. For every old dollar that goes in, nine new dollars come out, created with the stroke of a pen or the click of a mouse. As you may be aware, general deposits are loans by the bank depositor to the bank. However, banks can spin new loans out of old loans, creating a wheel of fortune by lending the same dollar to nine different customers—a feat that, to the uninitiated, is equally quite amazing and frightening!

This financial alchemy is perfectly legal and is in fact carried out with the aid and assistance of central banks everywhere, including our own Federal Reserve. If this wheel of fortune should hit a bump in the road and suddenly fall off its axle, causing the bank to crash, don’t worry because a central bank can do what no one else can legally do: counterfeit new money to set things right, a feat that “all the king’s horses and all the king’s men” cannot do!

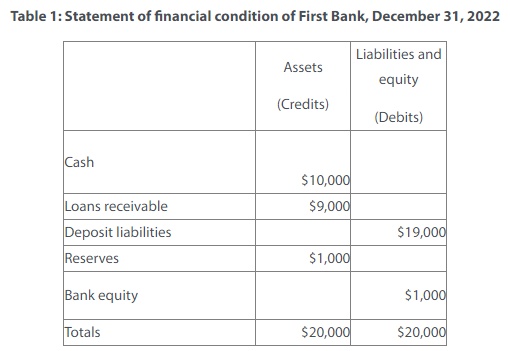

Let’s take a closer look at how fractional-reserve banking works. Customer A deposits $10,000 in a checking account at First Bank. First Bank records the cash in its books and credits customer A’s account. The cash is an asset of the bank (a credit), which is offset by the liability to customer A (a debit). First Bank now has cash to lend, subject to government reserve requirements. Reserve requirements, which are established by the Fed, specify the amount (expressed as a percentage of deposits) that a lending institution must hold in reserve, either as vault cash or on deposit with a Federal Reserve bank, in order to guarantee payment of customers’ deposits. The reserve requirement for “reservable” deposits greater than $36.1 million (as of January 3, 2023) at any lending institution has been traditionally 10 percent. As a result, First Bank is free to lend $9,000 of the deposited money, keeping $1,000 in reserve.

Customer B comes into First Bank seeking a car loan. First Bank agrees to lend customer B $9,000. First Bank credits customer B’s checking account for $9,000 and debits an asset account called “loans receivable.” As you will recall, bank loans to customers are “investments” and, therefore, are assets—not liabilities.

At the completion of these two transactions, First Bank’s statement of financial condition would look like this (for simplicity, I have assumed no other transactions).

Notice that the bank has deposit liabilities of $19,000 and cash on hand of $10,000. Let’s assume that the loan to customer B is for three years, payable with interest in monthly installments. The demand deposits (checking account balances) include the original deposit of $10,000 from customer A plus the proceeds of the loan to customer B of $9,000. Presumably, customer B will spend the loan money on a car in the next few days. Where did the loan money credited to customer B’s checking account come from? Out of thin air!

The wheel turns again when the car dealer deposits the $9,000 proceeds in his bank, Second Bank. Now Second Bank, like First Bank, is free to make loans, subject to the 10 percent reserve requirement. When the wheel finally stops turning, loans of $90,000 have been created on a cash base of just $10,000. As we have seen, that cash is itself a chimera—nothing more than debt wrapped inside more debt.

The table above demonstrates that banks can expand the money supply by a factor of ten when the reserve requirement is 10 percent. Historically, the United States reserve requirement has been 10 percent on transaction deposits, such as checking and negotiable order of withdrawal accounts (M1) deposits, and 0 percent on time deposits, such as deposits into savings accounts and certificates of deposit. The 0 percent reserve requirement on time deposits enables banks to expand the money supply by more than a factor of ten.

Some would argue that banks are not really “insolvent,” just at times illiquid—not always having ready cash when needed. However, that’s true only if we consider just one or a few banks at a time. Any bank having a temporary shortage of cash could always borrow the needed funds to make up for the temporary cash shortage. The problem, however, is that all banks are illiquid and, when pricked by some general financial shock, can easily slip into insolvency.

When the reserve ratio is 10 percent, total deposits are reduced by ten dollars for every dollar withdrawn from the banking system. Banks then have to call in loans or sell securities to cover their depositor’s demands for money. This “liquidity crisis” is the reason behind most financial “panics,” bank runs, and similar economic disturbances. It’s “debt on the way down,” but this time on a grand scale!

Effective March 26, 2020, the Federal Reserve reduced bank reserve requirements, get this, to zero! Even prior to this change, reserve requirements only applied to transaction accounts, nonpersonal time deposits, and Eurocurrency liabilities. Everything else was “jokers are wild.” Thus, banks could create as much funny money as the traffic would bear. When reserve requirements are zero, the ability to create money is infinite!

The Fed’s money manipulation is the root cause of our economic problems. Bubbles in housing prices, United States Treasury notes and bonds, and cryptocurrencies—to give but a few examples—and the recent failures of the Silicon Valley, Republic, and Signature banks can all be traced to our monetary policies.

The fundamental issue for most banks is that they are forced to invest “long” but borrow “short,” something no prudent finance manager would ever do. Checking and other demand deposits are short-term liabilities of the bank. Bank loans, such as car loans, are intermediate-term investments. Mortgage loans are long-term investments. Banks also invest in government securities to balance their investment loan portfolio. Investing “long,” however, subjects the bank to interest-rate risks because the value of their investment loan portfolio is inversely related to changes in interest rates. A thirty-year mortgage loan yielding 2 percent is only worth a fraction of a similar loan yielding 6 percent. To be more precise, a $100,000 investment in such an instrument would be worth only $44,280 if interest rates were to rise to 6 percent. If interest rates rise to 8 percent, the value would fall to $31,768, according to the bond price calculator.

Therein lies the trap that Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) fell into—with disastrous results. It’s the trap set by the very nature of fractional-reserve banking:

Over a period of just two days in March 2023, the bank went from solvent to broke as depositors rushed to SVB to withdraw their funds, resulting in federal regulators closing the bank for good on March 10, 2023.

SVB’s collapse marked the second largest bank failure in U.S. history after Washington Mutual’s in 2008.

That money created out of thin air should one day evaporate before our eyes should surprise no one, except perhaps Paul Krugman and his fellow court jesters at the New York Times. The endless cycles of boom and bust are a direct result of government manipulation of the money supply. It’s really that profound and that simple.

About the Author

Stephen Apolito is a CPA living in Bronxville, New York. A veteran of the US Air Force, Apolito is a graduate of Washington and Lee University and has taught in the New York City public schools.

Article cross-posted from Mises.

]]>When banks practice this kind of maturity mismatch—potentially immediate-term liabilities (deposits) backed by long-term assets (loans and Treasury securities), it is called “fractional reserve banking.”

The failure of SVB and other recent bank crises have reignited the debate over fractional reserve banking. While Austrian economists across the board are critical of central banking and government manipulation of the money supply and interest rates, there are differences of opinion on fractional reserve banking. Murray Rothbard was firmly against the practice for both economic and ethical reasons; however, “fractional reserve free bankers” (FRFB) like George Selgin and Larry White have written extensively about how fractional reserve banking per se does not make for an inherently unstable banking system and does not cause business cycles. The FRFB position is that the business cycles and instability are caused by government interference, primarily via central bank monetary policy.

To understand how fractional reserve banks operate, we first need to make a distinction between warehouse banking and loan banking. Warehouse banking refers to the way banks accept deposits and act on instructions from the depositor to send or withdraw money at par on demand. In warehouse banking, there is no multiplication of deposits or creation of credit—the bank simply stores, or “warehouses,” depositors’ cash. Importantly, depositors have to pay a fee for this service at warehousing banks.

Loan banking refers to the way banks can act as financial intermediaries. A bank customer can purchase a certificate of deposit or other time deposit that, importantly, represents a parting with funds. The customer cannot access these funds for spending or withdrawing. The bank uses these funds to extend loans. The interest earned on these loans is shared (according to the contract) between the bank, which administered and intermediated, and the customer, who relinquished the money. Here, there is also no multiplication of deposits, expansion of the money supply, or creation of credit ex nihilo.

The issues with fractional reserve banking come from combining these two functions: warehouse banking and loan banking. Banks combine these functions by using demand deposits (which depositors can withdraw at par on demand) as a basis for extending loans. Hopefully, the potential problems with this are obvious: What if depositors request more money than the bank has on hand, due to the fact that not all deposits have matching cash reserves, but instead are backed by long-term loans?

This is exactly what happened to SVB. Depositors wanted to withdraw more cash than the bank had in reserves. SVB had used depositors’ funds to purchase Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities, and to extend loans to high-tech firms. SVB might have had less foresight than other banks, but it is important to note that all banks do this sort of thing. No bank keeps 100 percent reserves—no bank keeps its warehousing and intermediation functions separate. In fact, in 2017 the Federal Reserve blocked a new bank that intended to be such a safe haven for depositors.

The repeated bank runs and associated financial crises caused by fractional reserve banking have led to the creation of central banking, government deposit insurance, a multitude of bank regulations, and a host of agencies to design and enforce these regulations. It’s worth pointing out, however, that if the government simply ignored bank runs, then the standard mechanisms of profit and loss would be at work. Banks would fail in the same way other private businesses fail. Potential bank customers would avoid unsound banks and flock to sound banks according to their own preferences and expectations. This prospect leads the FRFB crowd to conclude that fractional reserve banking per se isn’t a problem—it is the moral hazard and money creation by the government that causes all the problems.

In my view, the debates over the sustainability and ethics of fractional reserve banking suffer from poorly defined terms. If a deposit is defined as “redeemable at par on demand,” then that constitutes a promise by the bank to have the funds available at par on demand, meaning no loans are purchased with those funds. If a contract stipulates that the bank will offer accounts for which deposits are defined as such but then uses the funds to provide loans, then the bank is in breach of contract. If, however, the bank and the customer agree on a looser definition of the term “deposit,” such that deposits are not always redeemable at par, or are redeemable at par but sometimes with a delay, then that is their prerogative. It seems to me that such an arrangement is more properly called an “unsecured callable loan” and that if these coexisted with true, fully backed deposits on the market, the callable loans would trade at a discount against the fully backed deposits.

I also think that the debates over the sustainability and ethics of FRFB are less important than the economic consequences of fractional reserve banking. No matter what the fine print in a deposit agreement says (and the language is not standard, by the way), if depositors view their checking account balances as one-to-one money substitutes, then prices and spending patterns will reflect the depositors’ own net worth calculations and expectations of disposable income. If a bank expands credit on top of that via fractional reserve banking, then the supply of credit and interest rates no longer reflect the depositors’ underlying real savings and rates of time preference. This wedge is what triggers the boom-bust cycle.

This brings us back to the addict analogy. Suppose an addict had the ability to magically create, ex nihilo, his own stimulating drug, as fractional reserve banks can do with money and credit. Suppose that the negative side effects of using the drug could be spread to all other members of society, as central banks and government deposit insurance allow for fractional reserve banks. Would you expect moderation? Would you expect healthy outcomes? Or would you expect an endless cycle of highs and crashes?

About the Author

Dr. Jonathan Newman is an Associate Professor of Economics and Finance at Bryan College and a Fellow at the Mises Institute. He earned his PhD at Auburn University while a Research Fellow at the Mises Institute. He was the recipient of the 2021 Gary G. Schlarbaum Award to a Promising Young Scholar for Excellence in Research and Teaching. His research focuses on Austrian economics, inflation and business cycles, and the history of economic thought. He has taught courses on Macroeconomics and Quantitative Economics: Uses and Limitations in the Mises Graduate School.

Article cross-posted from Mises.

]]>