This tends to be the modus operandi of top establishment analysts, and the majority of economists out there simply follow the lead of these gatekeepers – Maybe because they’re vying for a limited number of cushy positions in the field, or perhaps because they’re afraid that if they present a contradictory theory they’ll be ostracized. Economics is often absurdist in nature because Ivy League “experts” can be wrong time and time again and yet still keep their jobs and rise up through the ranks. It’s a bit like Hollywood in that way; they fail upwards.

In the meantime, alternative economists keep hitting the target with our observations and predictions, but we’ll never get job offers from establishment publications because they’re not looking for people who are right, they’re looking for people that toe the line.

And so it goes. I look forward to the fast approaching day when all of these guys (and girls) proclaim frantically that “no one saw this crisis coming.” After things get even worse, they’ll all come out and say they actually “saw the crisis coming and tried to warn us.”

The hope is not so much to get credit where credit is due (because that’s not going to happen), but to wake up as many people who will listen as possible to the dangers ahead, and maybe save a few lives or inspire a few rebels in the process. In the case of establishment yes-men, the hope is that they get that left hook to the face from reality and lose credibility in the eyes of the public. They deserve to go down with the ship – Either they are disinformation agents or they’re too ignorant to see the writing on the wall and should not have the jobs they have.

The latest US bank failures seem to be ringing their bell the past couple of months, that’s for sure. In a survey managed by the World Economic Forum, over 80% of chief economists now say that central banks “face a trade-off between managing inflation and maintaining financial sector stability.” They now warn that price pressures look likely to remain higher for longer and they predict a prolonged period of higher interest rates that will expose further frailties in the banking sector, potentially compromising the capacity of central banks to rein in inflation. This is a HUGE reversal from their original message of a magical soft landing.

Imagine that. The very thing alternative economists including myself have been “ranting” about for years, the very thing they used to say was “conspiracy theory” or Chicken Little doom mongering, is now accepted as fact by a majority of surveyed economists.

But where does this leave us? After acceptance usually comes panic.

The credit crunch is just beginning and the absorbing of the insolvent First Republic Bank into JP Morgan is a median step to a larger crash. The expectation is that the Federal Reserve will step in to dump more stimulus into the system to keep it afloat, but it’s too late. My position has always been that the central banks would deliberately initiate a liquidity crisis through steady interest rate hikes. This has now happened.

The Catch-22 scenario has been accomplished. Just like the lead up to the 2008 credit crisis, all the Fed needed to do was raise rates to around 5% to 6% and suddenly all systemic debt becomes untenable. Now it’s happening again and they KNEW it would happen again. Except this time, we have an extra $20 trillion in national debt, a banking network completely addicted to cheap fiat stimulus and an exponential stagflation problem.

If the Fed cuts rates prices will skyrocket even more. If they keep rates at current levels or raise them, more banks will implode. Most mainstream analysts will expect the Fed to go back to near-zero rates and QE in response, but even if they do (and I’m doubtful that they will) the outcome will not be what the “experts” expect. Some are realizing that QE is an impractical expectation and that inflation will annihilate the system just as fast as a credit crisis, but they are few and far between.

The World Economic Forum report for May outlines this dynamic to a point, but what it doesn’t mention is that there are extensive benefits attached to the coming crisis for the elites. For example, major banks like JP Morgan will be able to snatch up smaller failing banks for pennies on the dollar, just like they did during the Great Depression. And, globalist institutions like the WEF will get their “Great Reset,” which they hope will frighten the public into adopting even more financial centralization, social controls, digital currencies and a cashless society.

For the average concerned citizen out there, this narrative change matters because it’s a signal that things are about to get much worse. When the establishment itself is openly acknowledging that gravity exists and that we are falling instead of flying, it’s time to get ready and take cover. They never admit the truth unless the worst case scenario is right around the corner.

Article cross-posted from Alt-Market. Image by 00joshi via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

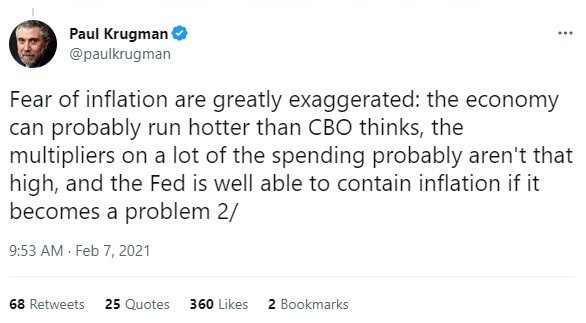

]]>Krugman expresses strong disagreement that the decline in interest rates caused bubbles and that the decline was artificial. For Krugman, the Federal Reserve sets short-term interest rates, which in turn determine long-term rates. He then suggests that there’s no such thing as an interest rate unaffected by policy.

The columnist then argues that what matters for the Fed’s policy is the natural rate of interest, which is consistent with price stability and economic stability—i.e., economic equilibrium. This means that the key objective of Fed policies should be to target the policy rate to the natural rate in order to attain this state of equilibrium. Given that the natural rate was trending down it is not surprising that the policy rate followed suit.

Why has the natural rate been trending down? According to Krugman, the downtrend was caused by demography. “When the working-age population is growing slowly or even shrinking, there’s much less need for new office parks, shopping malls, even housing, hence weak demand.” Krugman warns, “These demographic forces aren’t going away. If anything, they’re likely to intensify, in part because the rate of immigration has dropped off. So there’s every reason to believe that we’ll fairly soon go back to an era of low interest rates.”

Krugman also says that the Fed’s interest rate policy has been in line with the neutral rate, which fell very sharply. Again, the key reason for this decline is aging population and reduced demand for the investment in the infrastructure. However, does it all make sense?

Interest Rates and the Fed

Again, according to Krugman, the Fed is the key factor for the determination of interest rates via its control of the short-term interest rates. The Fed influences short-term interest rates by influencing monetary liquidity in the markets. Through the injection of liquidity, the Fed pushes short-term interest rates lower. Conversely, by withdrawing liquidity the Fed exerts an upward pressure on the short-term interest rates.

On this thinking, long-term rates are the average of current and expected short-term interest rates. If today’s one year rate is 4.0 percent and the next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5.0 percent, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5 percent ((4+5)/2=4.5 percent). Conversely, if today’s one-year rate is 4.0 percent and the next year’s one-year rate expected to be 3.0 percent, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5 percent (4+3)/2=3.5 percent.

On this logic, it would appear that the central bank is the key in the interest rate determination process. However, is this the case?

Individuals’ Time Preferences and Interest Rates

We believe it is individual time preferences rather than the central bank that hold the key in the interest rate determination process. What is it all about?

An individual who has just enough resources to keep himself alive is unlikely to lend or invest his paltry means. The cost of lending, or investing, to him is likely to be very high—it might even cost him his life if he were to consider lending part of his means. Therefore, he is unlikely to lend, or invest even if offered a very high interest rate. Once his wealth starts to expand, the cost of lending, or investing, starts to diminish. Allocating some of his wealth towards lending or investment is going to undermine to a lesser extent our individual’s life and well-being at present.

From this we can infer, all other things being equal, that anything that leads to the expansion in the wealth of individuals is likely to result in the lowering of the premium of present goods versus future goods. This means that individuals are likely to accept lower interest rates.

Note again, interest is the outcome of the fact that individuals assign a greater importance to goods and services in the present against identical goods and services in the future. The higher valuation is not the result of capricious behavior, but because of the fact that life in the future is not possible without sustaining it first in the present. Hence, various goods and services that are required to sustain a man’s life at present must be of a greater importance to him than the same goods and services in the future.

The lowering of time preferences—i.e., the lowering of the premium of present goods versus future goods due to wealth expansion—is likely to become manifest by a greater eagerness to invest wealth. With the expansion in wealth, individuals are likely to increase their demand for various assets—financial and nonfinancial. In the process, this raises asset prices and lowers their yields, all other things being equal.

As a rule, a major factor for the discrepancy between observed interest rates and the time preference interest rate is the actions of the central bank.

The Neutral Interest Rate Myth

Again, by popular thinking, the neutral rate is one that is consistent with stable prices and a balanced economy. Hence, by this thinking in order to attain economic and price stability, Fed policy makers should navigate the federal funds rate towards the neutral rate range.

By the neutral interest rate framework, in order to establish whether monetary policy is tight or loose it is not enough to pay attention to the level of money market interest rates, but rather one needs to contrast money market interest rates with the neutral rate. Thus if the market interest rate is above the neutral rate then the policy stance is tight. Conversely, if the market rate is below the neutral rate then the policy stance is loose. Hence, whenever the money market rate is in line with the neutral rate, then the economy is in a state of equilibrium and there are neither upward nor downward pressure on the price level.

In the popular framework, the neutral interest rate is formed at the point of intersection between the supply and demand curves. The supply and demand curves as presented by popular economics originates from the imaginary construction of economists. None of the figures that underpin these curves originates in the real world; they are purely imaginary. According to Ludwig von Mises, “It is important to realize that we do not have any knowledge or experience concerning the shape of such curves.”

Consequently, this implies that it is not possible to establish from the imaginary curves the neutral interest rate. The employment of sophisticated mathematical methods does not solve the issue that the neutral rate is not observed. So what are the basis for Krugman to suggest that the neutral rate has been trending down? None whatsoever. Contrary to Krugman, the Fed by being a major source for money creation has been instrumental in the formation of bubbles.

Conclusion

Contrary to Krugman the main source for money creation out of “thin air” is the central bank. Consequently, various bubble activities created are the outcome of the Fed’s monetary pumping and nothing else.

About the Author

Frank Shostak‘s consulting firm, Applied Austrian School Economics, provides in-depth assessments of financial markets and global economies. Contact: email.

Image by 00Joshi via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Article cross-posted from Mises.

]]>